As published in Converting Quarterly in Quarter 1, 2022 by E.J. (Ted) Lightfoot, Ph.D., principal, Ted Lightfoot LLC.

It is with a touch of sadness that I take over this column from my old friend and mentor, the late Dr. Edward Cohen. I would like to begin with the most important subject – an attitude really – that Ed helped instill in me. The concept of product-process integration (PPI) is simple: Processes and products both need to be appropriate for the needs of the application being served. At a conceptual level, that isn’t a hard sell, but at a tactical level, it can be hard to remember.

One aspect of product-process integration is ensuring the formulation will run on the coater. Sometimes this is called “Design for Manufacturing.” When I started with the DuPont Co., the engineers would shake their heads at chemists who took formulations into the plant with viscosities too high or too low to coat well. But my first project was something different: I inherited a product that was too sensitive to be manufactured in the kettles we had. We couldn’t adjust the chemistry to align with the process; we had to improve the mixing to handle the chemistry the market required.

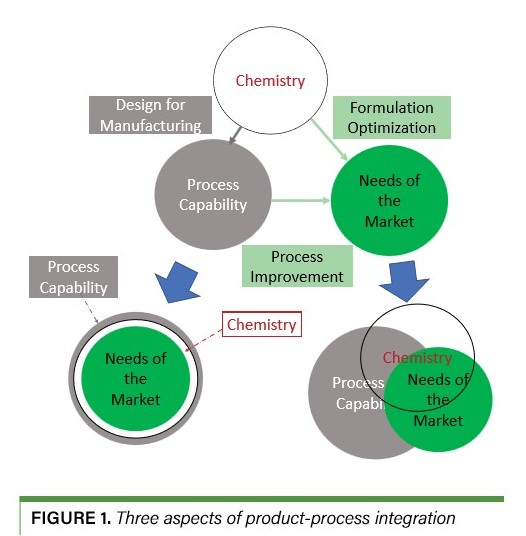

This second aspect of PPI – process improvement – is less common. Many companies are reluctant to make changes to processes that are fully commercial. But process improvement is not limited to hardware changes; it can include optimizing process settings [1]. The third aspect of product-process optimization is optimizing the chemistry to meet the needs of the market. This kind of product optimization also is familiar. Figure 1 shows two ways these activities can play out.

Hitting on all cylinders

All too often, we commit to only one of these activities. This can lead to the scenario shown on the lower right of Figure 1: We generate samples that are attractive and customers sign-off on, but the product generates ongoing complaints and/or has low yields. That was where my first project started. Customers had loved the qualification samples, but each new batch was different from the one before. Internally, only two of three batches were in limits even though extensive work was done to optimize the product during scale-up.

The preferred scenario is the one shown on the lower left of Figure 1: The chemistry is designed and can be controlled well enough to meet all the needs of the market, and the process is aligned with both market needs and product needs, giving us good process capability. PPI can proceed sequentially. For the mixing project, we improved our control of mixing, then tuned the rate of mixing to meet the market needs. The best way to get good process capability is to adopt the mindset that we are optimizing both the process and the product to meet the needs of the market (that we rarely can change). This is the mindset – and the toolbox – I will focus on in future column installments.

References

1. “Managing the coating window,” E.J. Lightfoot, Converting Quarterly 2021 Q3, pp. 68-74

Original article found online here.